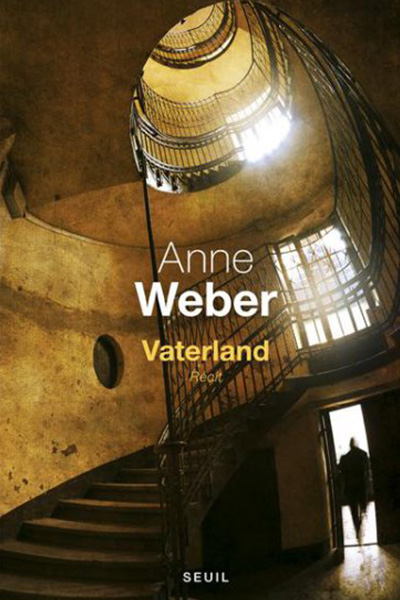

"Vaterland" by Anne Weber

"Vaterland" by Anne Weber Writing German identity

With "Vaterland', German writer Anne Weber walks in the tracks of her great grandfather, a Prussian intellectual and close friend of Walter Benjamin. In the background of her writing, the diary of a quest for identity.

A novel about origins

Writing a book can sometimes come from an intimate need, such as closing a burdening legacy. The book "Vaterland' is the result of this process. Writer Anne Weber left Germany to settle in Paris in the early 1980's.

The distance created was surely necessary to gain retrospective insight with the country, but also with the family she comes from. National and family community are both problematic entities for Anne Weber. Her grandfather on her father's side was a "convinced Nazi" and never wanted to meet her because she was born out of marriage. How do you accept the Germans' painful history when a piece of filiation is missing?

To better ponder on this, Anne Weber took a peculiar path. She avoids what seems to be the unthinkable (the Nazi period) to go back to the source of evil: how Prussia was before World War I, marked by an authoritarian and warmongering culture. It is not her grandfather the writer wants to figure out, but her great grandfather Florens Christian Rang.

Looking for Sanderling

Anne Weber likes comparing Humans and birds and decided to nickname her ancestor Sanderling, in reference to the little water bird she "often saw running along the water, going forward and backward depending on the tide". This is a perfect nickname for a study project that often went back and forth, lost in the "bushes of time".

"Vaterland" tries to answer a simple yet tricky question: who was Sanderling? A tormented intellectual, the man lived torn between Christian brotherhood and warmongering Prussianism. A philosopher minister, he was a close friend to Walter Benjamin and Martin Buber. But his memoires, still unfinished, fell into oblivion. He left behind drafts of essays kept in the Walter Benjamin Archives in Berlin and a few publications, including a book on Carnival translated in French.

Understanding the country of your fathers

Through her very dense writing, without any chapter or pause, interrupted by bursts of irony, Anne Weber offers a fascinating investigation on her own origins and the source of Nazi evil. Analyzing thoroughly the writings of her great grandfather, she starts to ask herself the question: do ideals have anything to do with blood ties? Is Sanderling responsible in any way in the deadly ideology defended later by one of his sons? Does Anne Weber herself have to consider herself as the heir of the ideas of the two ancestors?

In addition to the fine approach of identity and legacy issues, "Vaterland" is also worth reading for the accuracy of the language. Anne Weber is indeed perfectly bilingual. She translates her books herself from French to German or German to French, as is the case for this book. First published in her mother tongue with the title "Ahnen" (Ancestors), the book was published by Seuil under the name "Vaterland". A term meaning both "country" and "country of fathers". This linguistic ambiguity perfectly illustrates the duality of her quest for identity.